You know how, when searching online for a recipe, your heart sinks when you reach one of those blogs, and realise that you’ve got to wade through screeds of text about the author’s personal life before you get to the recipe… well, this post is a bit like that. Feel free to scroll down to the bottom if you just want to hear the song. I won’t be offended (I won’t know!). And, as I’ve probably commented before, I do these blog posts for my own personal satisfaction, and if anyone else likes them that’s just a bonus. So, here goes.

When I was about 8 or 9, two new, young, male teachers started work at my primary school – Mr France and Mr Snow. I was in Mr France’s class in what these days would be Year 5, and I think it’s fair to say that he was a popular teacher with all of the class – very different from some of the older, fiercer teachers in the school. My mother taught at the same school, and definitely fell into that older, fiercer category. She and Barrie France seemed to hit it off, however, and they stayed in touch, and continued to meet up occasionally, after he moved on to a different school. And so it was, I suppose, that finding himself with two spare tickets for a barn dance at Warehorne, he offered them to my Mum. She and My Dad had been keen dancers before I was born – old time, barn dancing, square dancing, but definitely not jive or rock & roll. When I was old enough not to need a babysitter, they started going out again, mostly to school PTA dinner dances. I resisted all my Mum’s attempt to teach me to waltz or foxtrot, but when the PTA put on a barn dance that was open to fifth formers and above, a bunch of us went along and – much to our amazement, I think – had a really good time.

I’ve been trying to work out when Barrie France’s offer of tickets to this dance at Warehorne took place. I can’t decide if it was early 1976, or early 1977. I’m pretty sure I’d already heard of, and heard good things of, local band Fiddler’s Dram, which suggests that the later date is more likely; but the internet tells me that the first Whitstable May Day celebrations were held in 1976, and I’ve very definite memories of attending that event (and I wouldn’t have known about it, but for this dance). In either case, it came after my Damascene conversion to folk song. And so, on that fateful Friday when my Mum told me that she and Dad were going out to a dance that night – and that the band included members of Fiddler’s Dram – I asked if I could come along too. A phone call must have ensued (this would have involved walking to the phone box at the end of the road – my parents didn’t get a telephone installed until I went to university) and a ticket was procured. Having previously only danced to one of those sedate EFDSS-style piano accordion and music-stand bands, I was completely blown away by the band that night – the Oyster Ceilidh Band. Their playing was so full of energy, and the dancing wasn’t sedate, it was energetic and enthusiastic – dancing with abandon. Well, if you’re a lover of what was become known as English Ceilidh then you’ll know what I’m talking about.

Warehorne residents Ron and Jean Saunders put on regular dances with the Oyster Ceilidh Band in the village hall. After that, we went to every one, and to Oyster dances elsewhere (Boughton Under Blean village hall was another regular venue). And soon a bunch of my school friends were coming along, attracted by the liveliness of the events, and joining in enthusiastically. There were other events that Ron and Jean helped to organise too – I recall a music hall evening, carol-singing round the village (see Week 174 – Sweet Chiming Bells) and a Harvest festival.

We’ll come back to Warehorne in a moment. But I also want to mention the other part Barrie France played in my folky journey. He’d begun organising an occasional (monthly?) folk club in a side room at the Stour Centre, the fairly new leisure centre in Ashford. His interests lay at the Simon and Garfunkel / Tom Paxton end of the folk spectrum, rather than the trad stuff I had become obsessed with, but I went along with my best mate Mike Eaton. It was Mike’s dad’s copy of Below the Salt that had switched me on to folk music, and we were now singing in unaccompanied harmony, our repertoire consisting entirely of songs pinched from Steeleye and Watersons LPs. As I wrote recently elsewhere

Our singing style was a horrible mixture of teenage Kentish boys trying to imitate Tim Hart (who, I later discovered, affected that country yokel voice, because he thought his actual public school voice was too posh), Martin Carthy in his still brilliant but most affected early 70s period, and the East Yorkshire vocal stylings of Mike Waterson – who was only in his mid-30s at the time, but sounded like he was one of the old ‘uns.

But imitation is the sincerest form of flattery, and it’s how most singers and musicians get started before, hopefully, finding their own way.

I have few memories of Barrie’s folk club. I think we might have gone along a couple of times at most, and I suspect that the club was a fairly short-lived venture. I do recall a Dutchman singing ‘It takes a worried man to sing a worried song’, and I think Ron and Jean Saunders might well have been there, performing with their son Jonathan (they later formed the Isle of Oxney Barn Dance Band, who were the first band I ever sat in with at a real dance in front of paying punters, and who I think might still be going, with Jonathan at the helm). And of course Mike and I would have sung – maybe ‘Spotted Cow’ or ‘Rosebud in June’, or perhaps ‘Swarthfell Rocks’, or ‘Bellman’, and almost certainly ‘Country Life’. The most important thing that happened, was that at the end of the evening we got chatting to a group of four girls. They hadn’t sung, but said they’d like to, and in the blink of an eye, we’d decided to form a group! The following Sunday afternoon, we all assembled in my Mum’s front room. There was Mike and me, and then Susan Hamlet, Lindsay Edwards, Caroline Chappell and ‘Bobo’ Woodruff (who declared that Mike, curled up in an armchair, looked like a dormouse). We’d just started sixth form, and they were a year older, in the Upper Sixth. I can’t actually remember if the six of us were ever all in the same place at the same time ever again, and this meeting certainly didn’t lead to us being a regular group (did we ever sing anywhere at all? I’m not sure we did). But Mike and I became good friends with Su Hamlet, and I learned a lot from her, one way and another (having eaten my Mum’s Sunday lunch one week, she told me that it had been horribly overcooked, and the beef was like tough old leather – not having much experience of other people’s cooking, this had never occurred to me, but actually she was absolutely correct!).

For his birthday that year, quite by chance, Mike was given a copy of the single LP selection from the Copper Family’s Song for every season and within the space of a couple of weeks we’d added almost all the songs from that record into our repertoire, Mike playing Ron to my Bob. And then, by the following summer I should think, we started singing with Alison Inns (sister of a school friend’s girlfriend) and Gill Harrison (sister of another friend in our year at school) and, sometimes, Jon Jarvis, who was slightly younger than us but whom we knew through the school choir and orchestra (Jonathan could actually play his instrument, which I’m not sure was really true of Mike with the violin, and definitely not of me with the trumpet). Mike’s Dad came up with our band name – Gomenwudu, which I believe is the name given to a harp in Beowulf (but I may have got that bit wrong). I don’t think Jon made it to Warehorne dances very often, but the rest of us did and, with the uninhibited arrogance of youth, we’d sometimes ask John Jones or Cathy Lesurf if we could sing a few songs at an Oyster ceilidh. And, bless them, they let us. And the audience were too polite to boo.

To put this in context, there were always song spots at these dances. Often from Fiddler’s Dram, or Beggars Description (see Week 277 – The First Time), or John Jones singing in harmony with his friend John Taylor; and, sometimes, John Jones would sing ‘The Barley Raking’ with Cathy Lesurf. So all of a considerably higher standard than anything we could aspire to.

There was one evening when we’d sung two or three songs at a Warehorne ceilidh, and they seemed to go down really well (cf. Samuel Johnson’s dog walking on its hind legs, and all that), and we were buzzing. To the extent that at the end of the night we mobbed John Jones and more or less forced him to dictate to us the words of ‘The Barley Raking’. Which meant that we had one more song in our repertoire! And I’ve sung it in various combinations ever since. Mike, Alison, Gill and I sang it unaccompanied; I sang it in my student days with Caroline Jackson-Houlston, again, unaccompanied; I worked up an accompaniment and arrangement in the early 1990s and played it with Saint Monday (with Dave Parry and Carol Turner); and then, when I started doing stuff with Magpie Lane fiddler Mat Green, we revived the same arrangement. And now, after more than 20 years of playing as a duo, Mat and I have finally recorded an album, and this song is on it.

The CD is called ‘Time for a Stottycake’ and you can see the track list, and purchase a copy (more than one, if you insist) from our website: www.andyturnermusic.uk/mat_andy.

The Barley Raking

Andy Turner – vocal, C/G anglo-concertina

Mat Green – fiddle

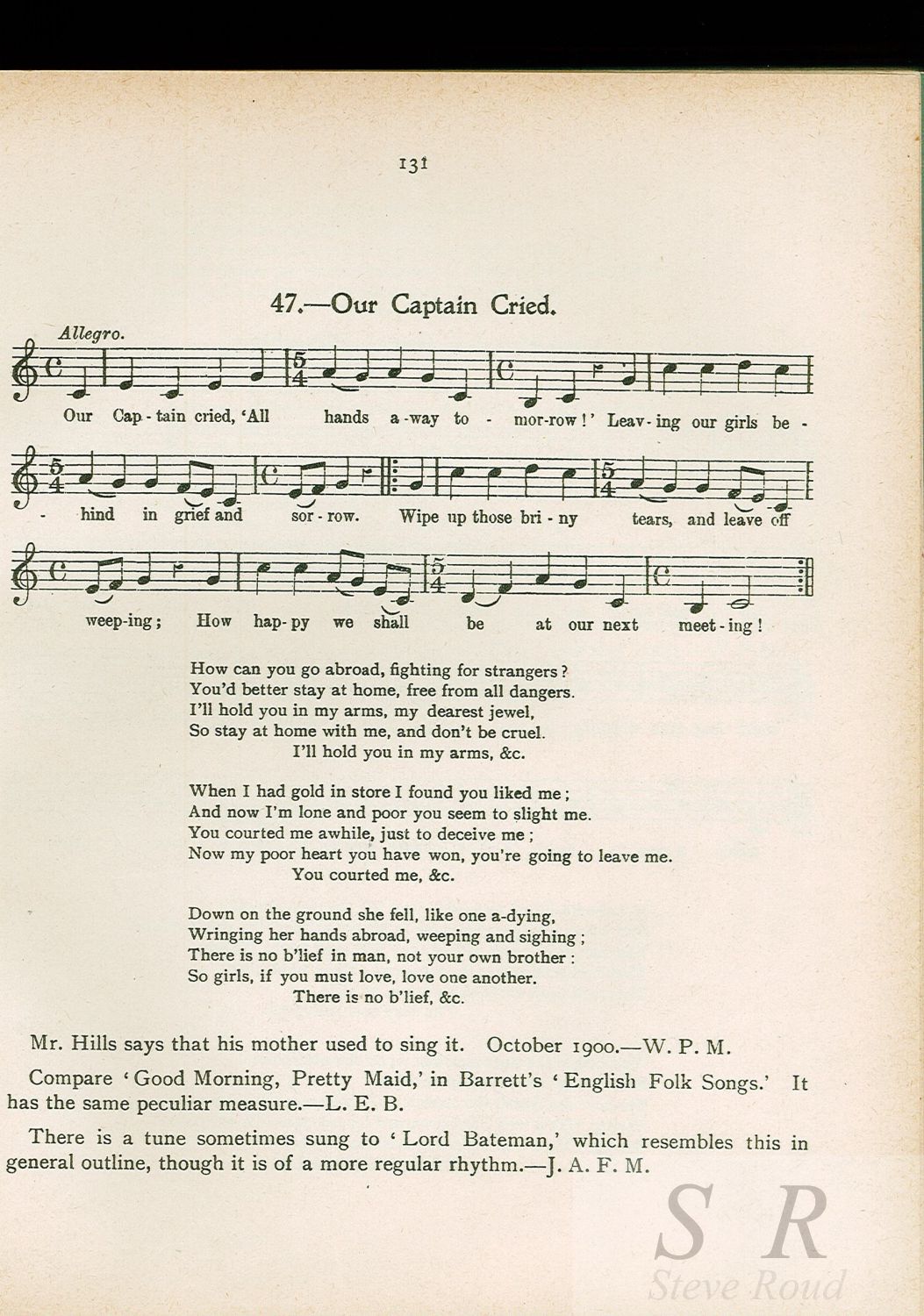

The song was collected in Hampshire by George Gardiner. It was included in Frank Purslow’s book The Wanton Seed and I’ve no doubt that that is where John and Cathy would have learned it. The notes to the revised edition of The Wanton Seed, by Malcolm Douglas and Steve Gardham, say that Purslow collated three Hampshire versions as well as inserting one verse from a broadside. The morris tune that runs through the arrangement is ‘Maid of the Mill’ from Kirtlington in Oxfordshire. The slightly asymmetrical B music is as per the musical notation I had from Tim Radford (written out, I assume, by Barbara Berry), but when I played it back to Tim he told me that’s not how it’s played for the modern Kirtlington side.

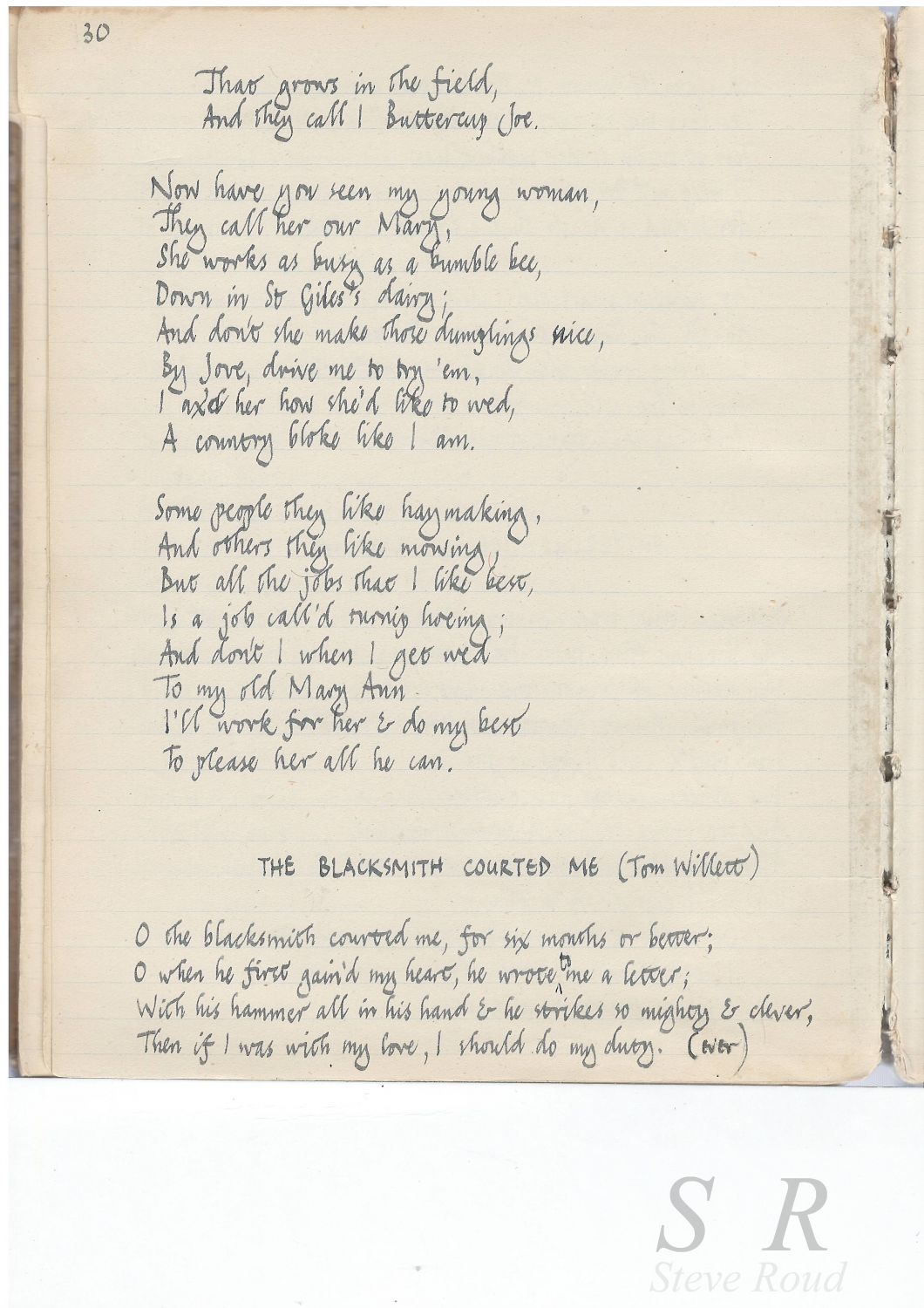

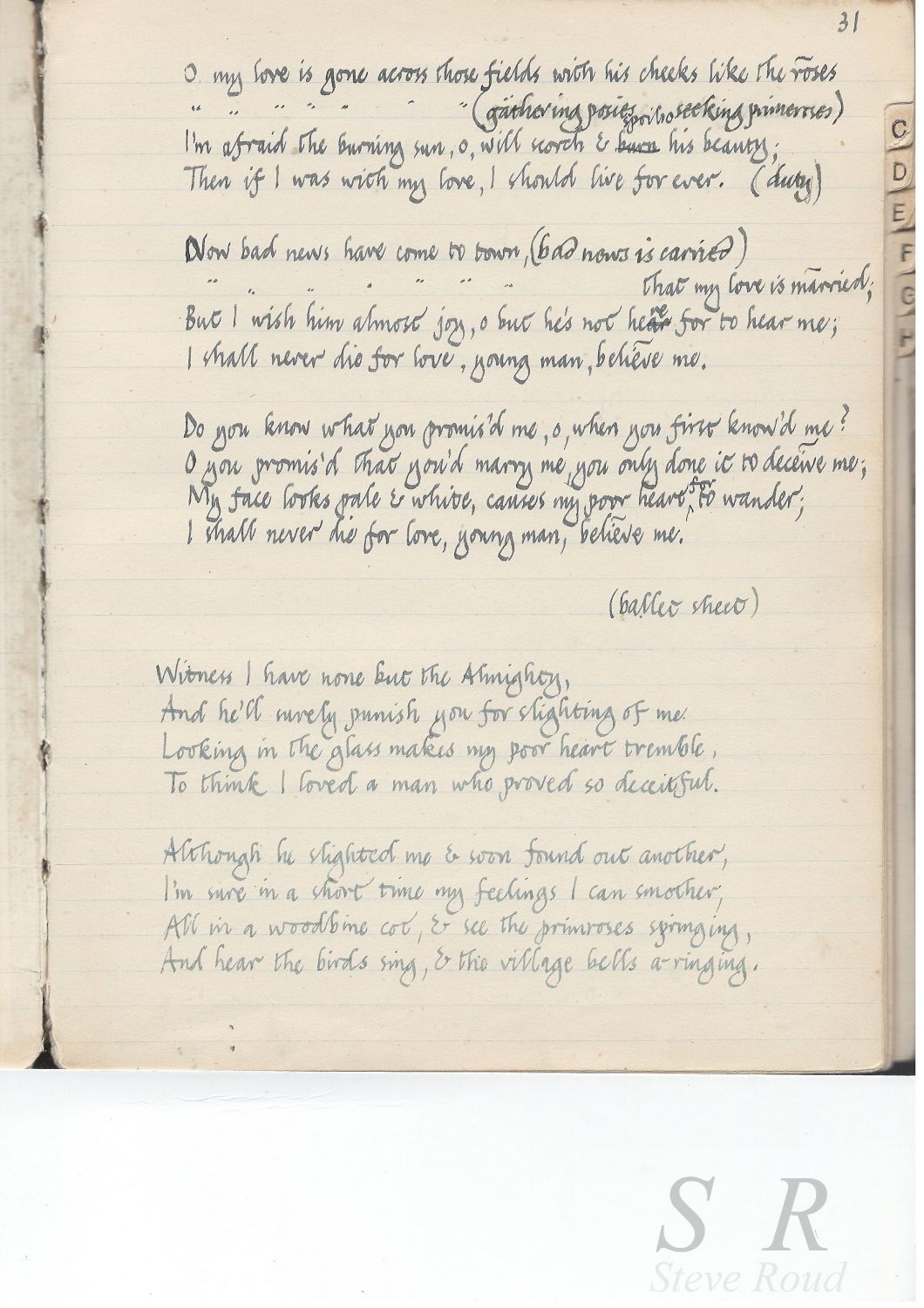

Barley Raking – broadside ballad from the Bodleian collection

A couple of concluding comments.

First, I’ve used the phrase earlier “the uninhibited arrogance of youth”. I have to say that, as a youth and, to be honest, probably throughout my life, I was far from uninhibited. And not especially arrogant either (although, as an only child, no doubt very selfish and not really aware of other people’s feelings). And yet, inspired by a love of singing, and the desire to do it as much as possible, we did somehow have the nerve to ask if we could sing at those Oyster ceilidhs. I wince now at the downright cheek of it, but we were so chuffed when the band let us.

Second, for anyone who’s confused, the phrase “cock up my beaver” refers to a beaver hat.

And finally, I have to record the passing of my dearest friend Mike. We saw each other infrequently in recent years, but I always considered him my best friend, as he had been since the age of 11. We had so many private jokes, that frankly weren’t really funny, but always made us laugh, if only because of the memories they evoked. Now I have noone to share those with. But the happy memories will live on. RIP Mike.

Mike and Andy at Dungeness, circa 1972