General James Wolfe was one of those dashing military heroes of the British Empire so much admired in the Victorian and Edwardian eras. A successful military commander Europe in the seemingly endless wars against the French in the eighteenth century, in 1758 William Pitt offered him the opportunity to fight them also in North America.

In March 1759, prior to arriving at Quebec, Wolfe had written to Amherst: “If, by accident in the river, by the enemy’s resistance, by sickness, or slaughter in the army, or, from any other cause, we find that Quebec is not likely to fall into our hands (persevering however to the last moment), I propose to set the town on fire with shells, to destroy the harvest, houses and cattle, both above and below, to send off as many Canadians as possible to Europe and to leave famine and desolation behind me; belle résolution & très chrétienne; but we must teach these scoundrels to make war in a more gentleman like manner.” (Wikipedia)

After laying siege to Quebec for three months, on 13 September 1759 Wolfe led a daring early morning assault which took the French by surprise (was that really gentleman like?). They were defeated in only fifteen minutes – a defeat which opened the way for the British taking control of all Canada; but, as this song records, Wolfe was fatally shot in the moment of victory.

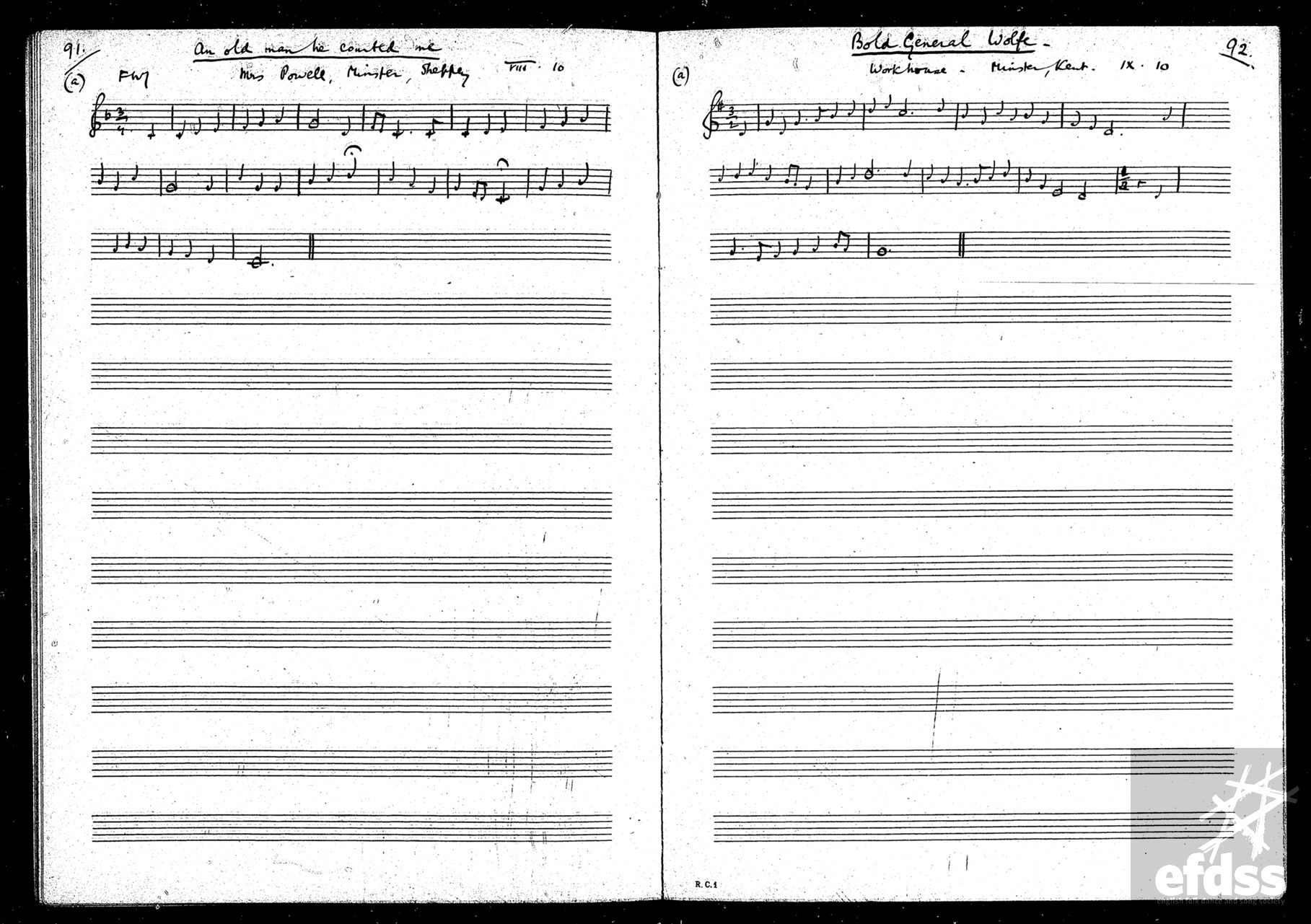

I originally heard the song on, and learnt it from, the Watersons’ eponymous 1966 LP. I’m indebted to George Frampton for alerting me to this Kentish version, some years before the EFDSS Take Six / Full English archive made the work of the early twentieth century collectors so much more accessible. It’s from the George Butterworth collection, but was actually noted down by Butterworth’s friend Francis Jekyll, nephew of the famous garden designer Gertrude Jekyll. Unfortunately we don’t know any details about the singer of the song, other than the fact that in September 1910, he or she was resident in the Workhouse at Minster, on the Isle of Sheppey in Kent.

Bold General Wolfe, as collected by Francis Jekyll in Minster, 1910. From the VWML archive catalogue.

Jekyll noted only the tune, not the words, so I carried on singing the verses I already knew, from Frank Puslow’s Marrowbones / the Watersons.

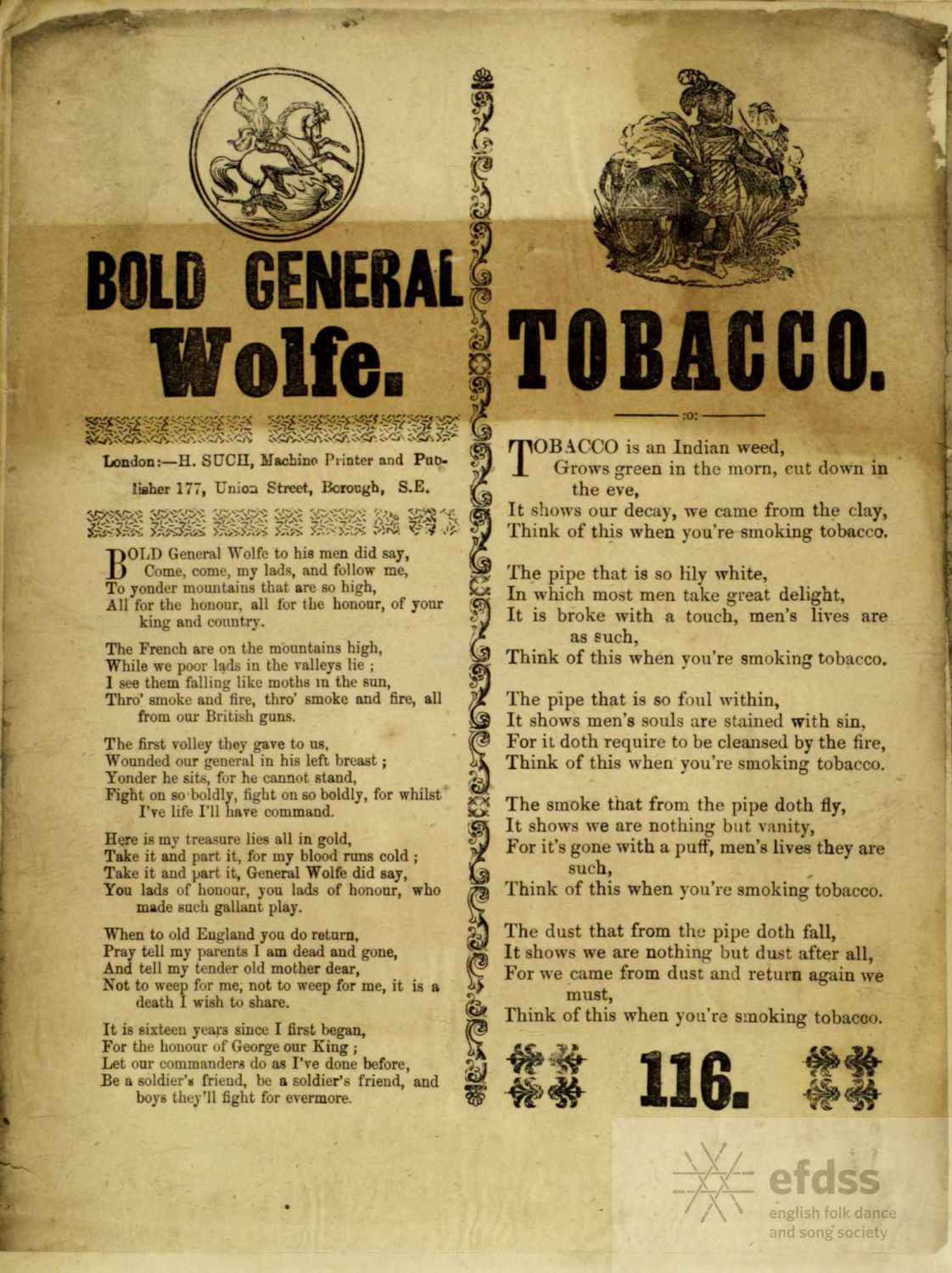

Looking at the collected versions, it’s clear this was a popular song, in the South of England at any rate. And, of course, there were numerous broadside printings.

Bold General Wolfe – Such broadside from the Lucy Broadwood collection, via the VWML archive catalogue.

James Wolfe actually had Kentish connections. Not with the Isle of Sheppey, as far as I’m aware, but with Westerham, where he was born in 1727, and where a statue was erected to his memory in 1911.

Statue of James Wolfe, Westerham, Kent after being unveiled by Field Marshall Roberts, 2nd Jan 1911.

Bold General Wolfe