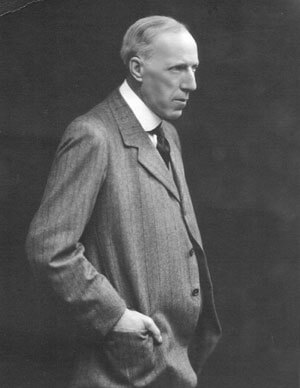

This Sunday, 23rd June 2024, will be the centenary of the death of Cecil Sharp, so I thought I should post a recording of one of the roughly two and a half thousand songs which he collected in England between 1903 and 1924 (the vast majority of these actually noted down between 1903 and 1914).

Sharp was, according to Steve Roud in his magisterial Folk Song in England,

by far the most active collector, researcher and publisher in both song and dance, and, like him or loathe him, he was the single most important figure in the study of folk song and music that we have had.

Vic Gammon summed him up thus, in an introductory essay to the EFDSS publication Still Growing (a good collection, still available from the EFDSS shop)

Cecil Sharp is the most important folk song and folk dance collector that England ever produced. His achievements were, to quote Mike Yates, ‘truly monumental’. His collection of material is many times larger than any comparable English collection. He wrote the first important book on folk song. He popularised folk song and dance as recreational forms in the twentieth century. He created a national institution, since 1932 known as the English Folk Dance and Song Society. Perhaps most interestingly Sharp is still the subject of heated, sometimes vitriolic debate and this is indicative of his influence and significance.

This introductory page on Sharp on the VWML website gives a good overview of his achievements, and of the controversies associated with him, both during his lifetime and since.

I have, over the years, read a fair bit about Sharp: A.H. Fox Strangways’ rather adulatory, non-critical 1933 biography; the critical (in Harker’s case extremely critical) examinations of the English folk revival by Dave Harker and Georgina Boyes; and some at least of C.J. Bearman’s revisionist work, which sought to exonerate Sharp whilst denigrating the Marxist Harker. Mike Yates provided a good summary of the arguments and counter-arguments in the article ‘Jumping to Conclusions’ on the Musical Traditions website. And more recently David Sutcliffe has produced a very well-researched, readable and balanced biography of Sharp, Cecil Sharp and the Quest for Folk Song and Dance.

You can, of course, make your own mind up. But in the meantime let’s enjoy (and keep on singing) the many great songs that Sharp collected. I’ve posted a good number of songs collected by Sharp on this blog. Particular favourites would include Master Kilby and The Brisk Young Widow – both songs which, had Sharp not noted them down would have been lost to posterity; also A Cornish Young Man, Shepherd Haden’s Young girl cut down in her prime, Poor Old Horse, Floating down the tide and all of those wonderful carols which he came across, primarily in the Welsh border counties of England.

Because it’s where I was born and bred, I’ve always had a particular interest in songs that were sung in Kent. Sharp spent very little time in the county, but he did collect a dozen songs in the neighbouring villages of Ham Street, Ruckinge and Warehorne on 23 Sept 1908. I’ve already posted a few of these songs from Kent, and here’s one more, collected from Sharp’s most important Kentish source, James Beale.

If you’re used to the Planxty version you’ll notice that there’s a verse missing here. Christy Moore (who learned the song from Mike Harding) has a verse where the young lady gives reasons why she shouldn’t open the door to the sodden soldier:

“My father’s walking on the street

My mother the chamber keys do keep

The doors and windows, they do creak

I dare not let you in – O”

That verse is not there in the version collected from James Beale – the woman doesn’t even pretend to place objections in the soldier’s way, but just comes straight down and opens the door. I suspect Planxty’s extra verse was added in from the Scottish song, ‘Let me in this ae nicht’, either directly, or via the version of Cold Haily Rainy Night (both have the same Roud number as Cold Blow and a Rainy Night) given in Stephen Sedley’s 1967 book The Seeds of Love. Sedley concocted a very singable version – so singable it was taken up by Martin Carthy and became a folk scene staple – but his notes to the song make it clear that he’d assembled it from a number of sources:

From the 19th century broadside in the Baring-Gould Collection, collated with a set collected by Sharp and with the Scots song Let me in this ae night published by Herd in 1779. The tune, known in the 17th century as The Gown Made New, is collated here from Johnson, Scots Musical Museum and from the version in the Caledonian Pocket Companion, 1752.

Cold blow and a rainy night

Andy Turner – vocals, C/G anglo-concertina, one-row melodeon in G

Leave a comment